In much of Bacon’s work, and certainly in the present painting, there seems to be an exemplification of the nineteenth-century French poet, Arthur Rimbaud’s advocacy of the deregulation of the senses in order to achieve free understanding. This does not merely occur formally in Bacon but in his very concept of human existence.

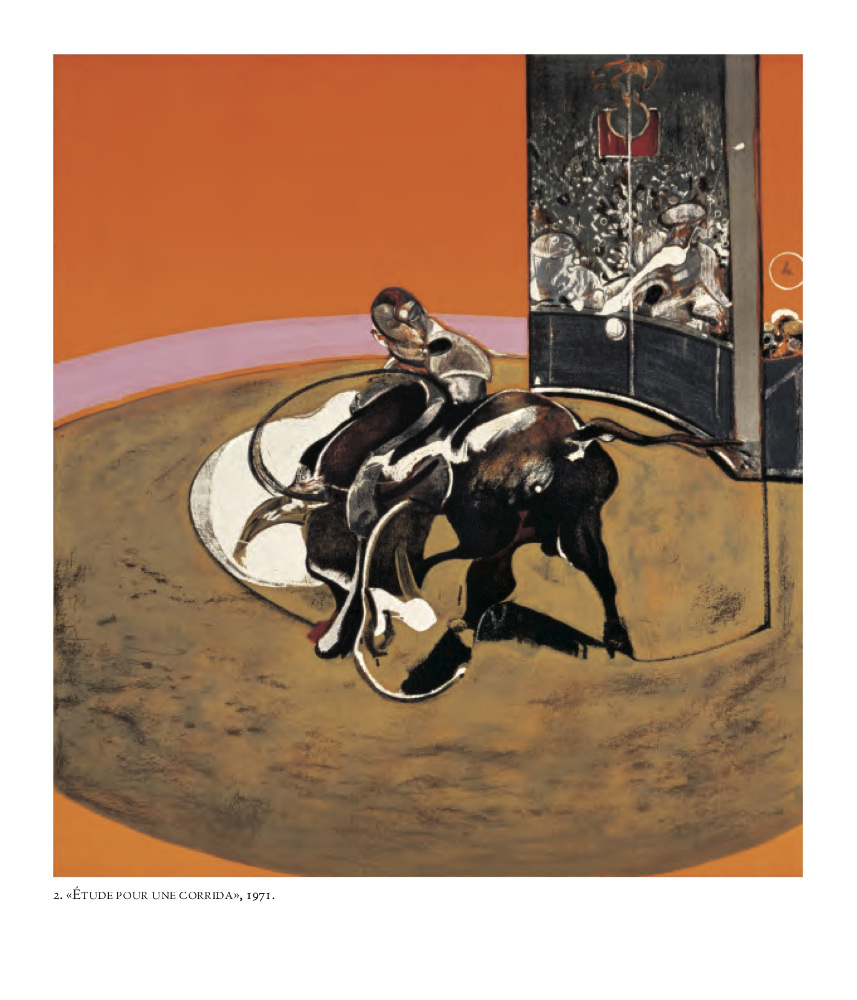

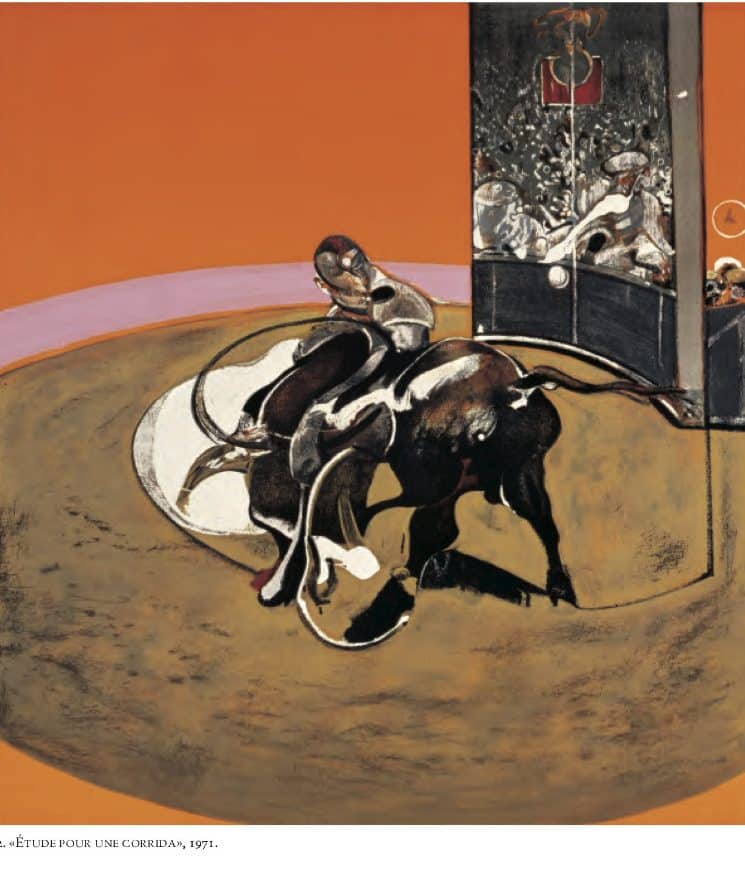

In the present painting, the swirl of virulent action of matador and animal blurs outlines and makes nebulous what would be definition, thus embroiling the spectator in a visual and disorienting maelstrom.

The matador’s and the bull’s senses are granted licence through their physical vigour while those of the spectator are granted licence through the excess effected upon their perception by the muddied perceptual data of this pictorial world.

In the white ectoplasmic connection between bullfighter and bull is the transcendence of physical discreteness and a deregulation of the mode and locale of identity associated with the physical body. The matador and bull also fuse formally and coloristically – the torsion of the matador and the steep bow of the bull’s forequarters align in unity and the upturned rearward-facing matador, combined with the bull’s lowered head form a Janus-like amalgam, though one must be guarded about the application of mythological or literary signifiers to Bacon as he sought primarily to convey the visceral immediacy of an action or state of mind. However, it is justified in this case to see a mythopoeia of a unifying violence sanctified by this very mythologisation because Bacon’s violence presents the thing itself in raw fashion while simultaneously removing it from verisimilitude and the rational, ordered vision of the sensible world.

The grey loop encircling the sternum of the fighter and the shoulder of the bull echoes the colours of both the taurine flesh and the matador’s apparel, and binds exclusively both bodies in a sort of profane paroxysm. The underlying white effluxion could perhaps be of a spiritual import as if it is the supra-linguistic spectre of union that defies conventional taxonomic rules and identities – neither protagonist is either man or beast, or both protagonists are both: by their conflict, which subsumes their separateness, the bullfighter’s face is animalised by an unnatural rictus, not to portray him as an animal but to neutralise his humanity perhaps. Similarly, the bull’s face is occluded, shearing from him his animal identity and re-creating his being as pure act, the nature of which for Bacon typifies both humanity and animal nature.

Any argument for an unequal duality of dominance (the looming matador) and submission (the bowing bull) thus must be erroneous. What is seen, rather, is a complex of reciprocity and undulation of the performativity of dance or, rather, a danse macabre. Suggestive within this concept of the painting as a dance is the Nietzschean idea of the Dionysian: that is the abandon and fervour residing in the human psyche that is creative, terrible, ecstatic and destructive. It is, depending on perspective, supra- or infra-rational and therefore the opposite of the serene and orderly Apollonian. To apply Nietzsche’s polarity here is far from arbitrary given Bacon’s fascination with the iconoclastic philosopher.

If Apollonian decorum can be discerned, it is in the shallow screen containing the onlooking crowd and the political ensign which perhaps alludes to the social sanction of a violence of a cathartic quality – a necessary release that preserves the political order by allopathic means. Yet, by the negligible width of the screen, Bacon illustrates political order and social quiescence as a literal facade, the depth within being illusory. So we have a brittle veneer of order that is disrupted by the subversive extension of the belligerent bull’s tail and the spectral splash on the screen that answers investment to the sacred and mythic act of violence.

Here too is a modulation of Rimbaud’s meaning: deregulation of the sense, in the sense of the rational thought that is conventionally the preserve of man, or perhaps the renewal of man’s pre-rational primitivity. Seen like this, the painting casts reason as an affected caparison of a culture through which the true, bestial and brutal moorings of the human psyche are concealed under a film of often opaque but always deluded equanimity. As Bacon flays the matador’s face to dehumanise him, he strips essential human/animal nature of its incidental ornamentation and its cultural pretensions. Beneath the glowing complexion of seraphic innocence, havoc and monstrosity range. This is the deregulation of the sense in terms of forgoing demure modesty and restraint, a yielding to the dark heart that batters at the gates guarding a manufactured sensibility. The Apollonian is become fiction while Dionysian uproar is the stuff of blunt reportage.

By: Shane Lewis

I really love your site.. Pleasant colors & theme. Did you develop this site yourself? Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my very own site and would like to know where you got this from or what the theme is named. Thank you!