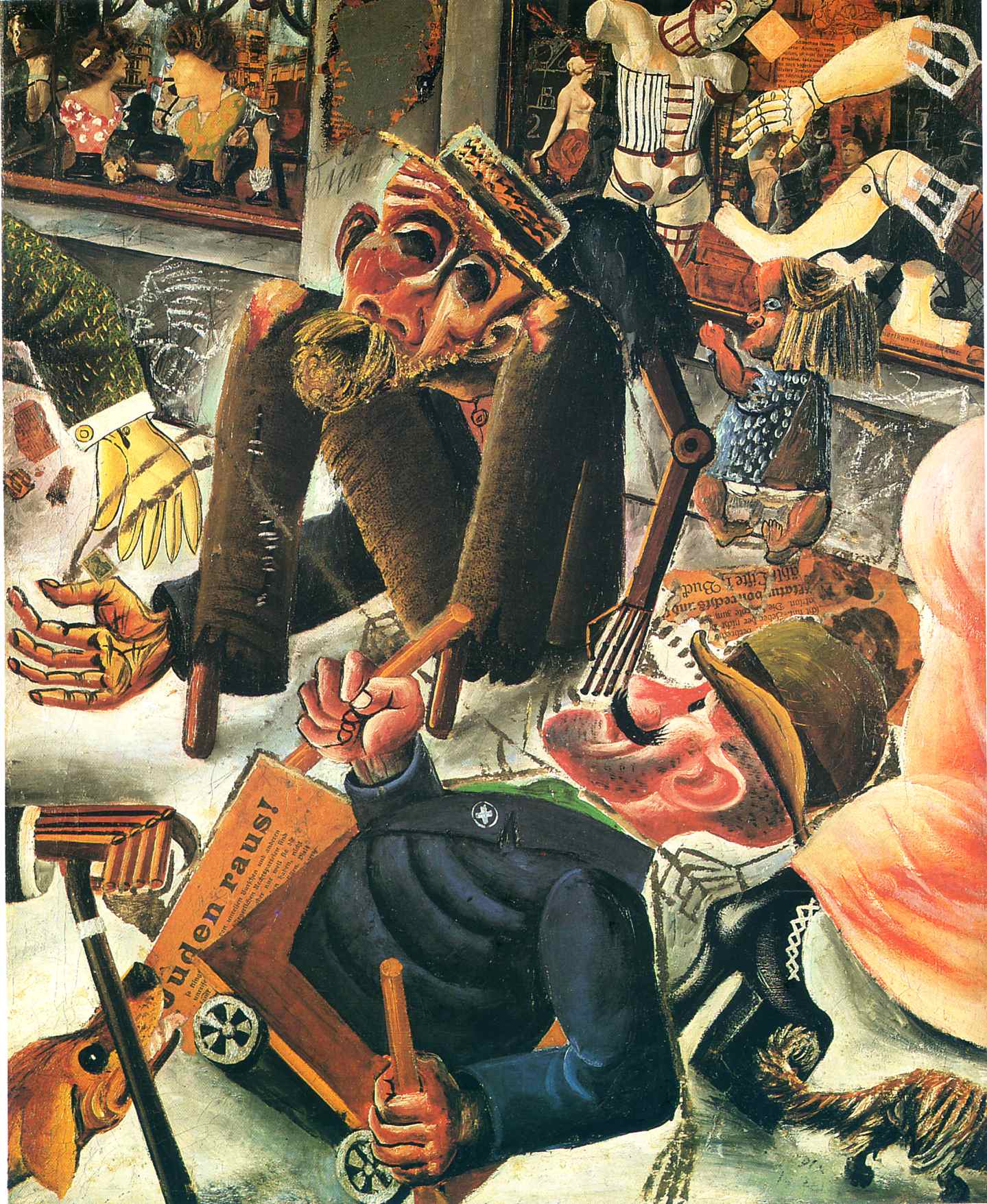

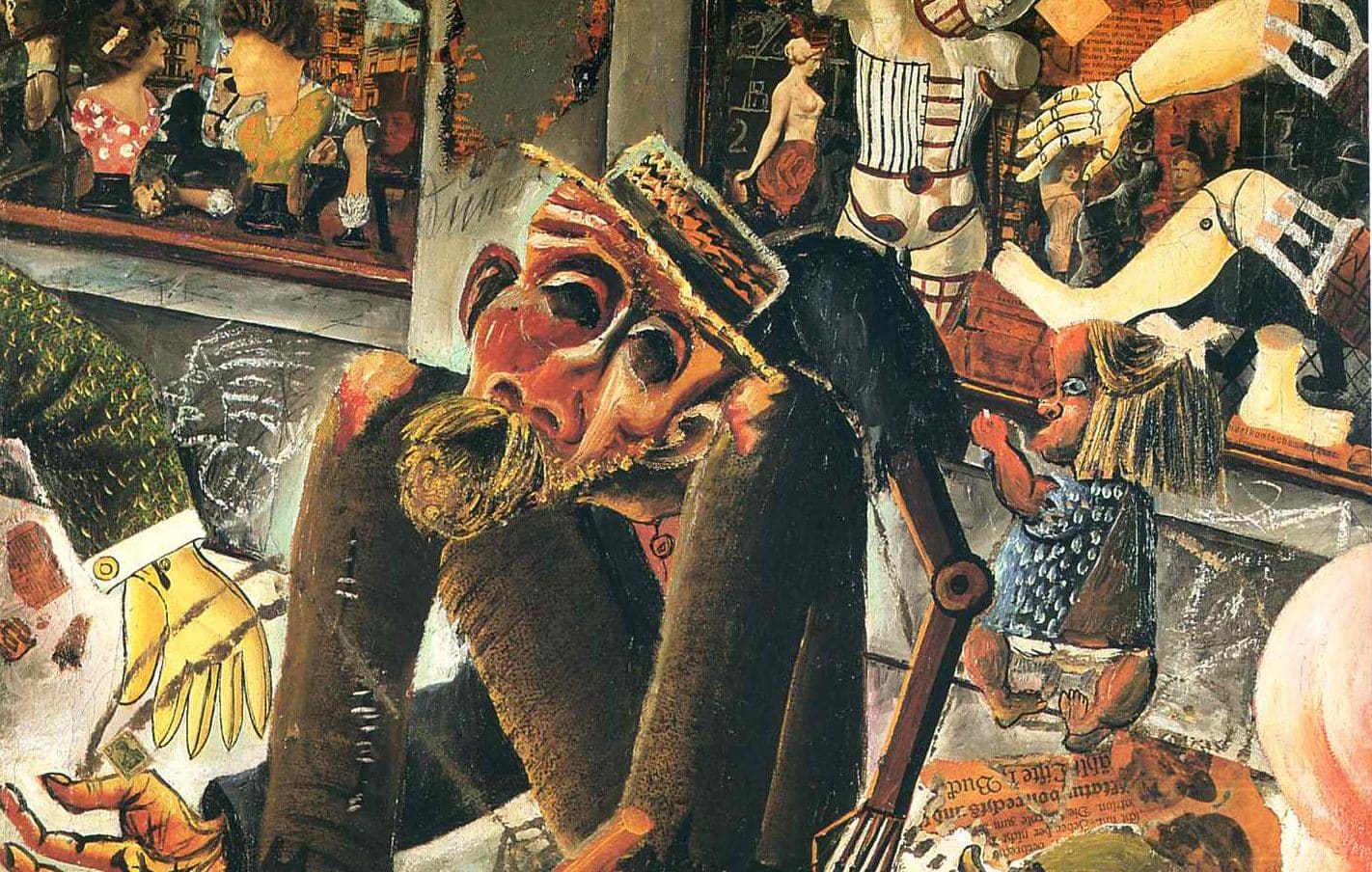

Francis Bacon visited Weimar Berlin in 1927 at the age of 18 accompanied by a certain Harcourt-Smith at the behest of Francis’ father. At the time Germany had entered a retrospectively-termed ‘golden age’ after World War I, subsequent political turmoil and near-economic catastrophe, and was a respite before the crazed fervour and conflict to come. The prevailing social and cultural climate was celebratory and self-indulgent which disgusted many. A new school of art called Neue Sachlichkeit (‘New Objectivity’) emerged which sought in unflinching realism to depict the lifestyle and perceived immorality of contemporary Germany. A leading light of the movement was Otto Dix. His Pragerstrasse portrays a place heaving with tension – the incipience of rabid racism, the dehumanising effects of war, profiteering, the apathy of the vain fashionista, the dismembered mannequins in the shop window form a mocking counterpoint to the war veteran’s injuries: he has served his purpose, by killing and being maimed, of helping to inaugurate a global consumer economy that is now loath to furnish him with the means to subsist.

This is Bacon’s Berlin, which had an enormous effect on his sensibility: a wafer-thin veneer of voguish behaviour fissuring to reveal egotism and the ubiquitous threat of violence. However, Bacon’s response, at least on the evidence of his art, displayed more in common with older artistic Expressionism; he stripped away the veneer as in Neue Sachlichkeit but could or would not maintain the icy distance of objectivity. What was essential for the ‘New Objectivists’ was social commentary, for Bacon it was the exploration of the cavernous and disturbing interior subjectivity, the necessity of figuration as a means to this in art was transformed by Bacon into a shared goal: the subjective aesthetic choices of the artist and the physical act of painting as means, on one hand, to the revelation of the interior via the representation of the physical state of flesh of the subject – the subjectivity and physicality of the artist-as-human transposed into the subjectivity and physicality of the human-as-subject, Bacon thereby, but without renouncing his agency of choice, implicates himself in his subject.

Bacon’s relationship with Expressionism is typically not one of rectilinear influence. To take the question of the use of colour: Expressionists deployed swathes of non-naturalistic hues in their compositions to effect an utter severance from the verisimilitude of the real, tangible world and to immerse their aesthetic in the hysterical or nebulous modes of subjectivity.

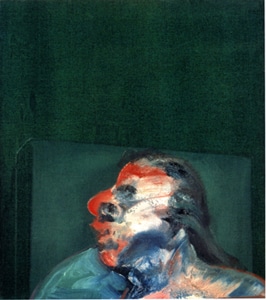

Bacon generally uses colour in conformity with those of the external world – most often the reds and pinks of lacerated flesh, in addition to the darks of rot and scatology. What Bacon does deploy in consonance with the Expressionist vision is his distortion of figurative form to transmit outwards the interior state of subjective emotion.

Expressionism emerged as an artistic response to the perceived dehumanisation resulting from rapid industrialisation and urbanisation in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These artists felt that these societal changes reduced human beings to incomplete and indistinguishable economic instruments. A correlative of this attitude was the rejection of Realism as an aesthetic movement – the imitation of nature in art was increasingly seen as a slavish fatalism or even an evasion. Expressionism’s goal became the ‘aestheticisation’ of a trans-rational inner subjectivity. Here Expressionism and Bacon diverge: while Bacon does (perhaps with the tangential exception of the ‘pope’ pictures) shear from his vision political signification, there is no sanctity accorded to a supposed immaculate spirit or subjectivity. To take the portrait of Muriel Belcher from 1966, the subject is painted in ‘full-face view’ which usually permits the portraitist to exclusively explore psychological states, Bacon chooses to physically flay the sitter, the effect being a ‘bleeding’ of the corporeal into the supposed rarefied realm of the mind but Bacon’s technical act of flaying demonstrates that the bleeding is no organic process but the result of the invasion of violence. While the Expressionists largely turn away from the tactile world because of its social and political corruption of the human soul, Bacon engages with this world but cuts from it the vestiges of its civil ornamentation and exposes what he sees to be the violent kernel of existence, redolent of the vision of the future in Orwell’s 1984: “imagine a boot stamping on a human face forever”.

Bacon’s dread is not typified by violence itself however but both the anticipation of it and its traumatic aftermath – the emphasis on ‘imagining’ the imminent violence and the reflexive pain deriving from it.

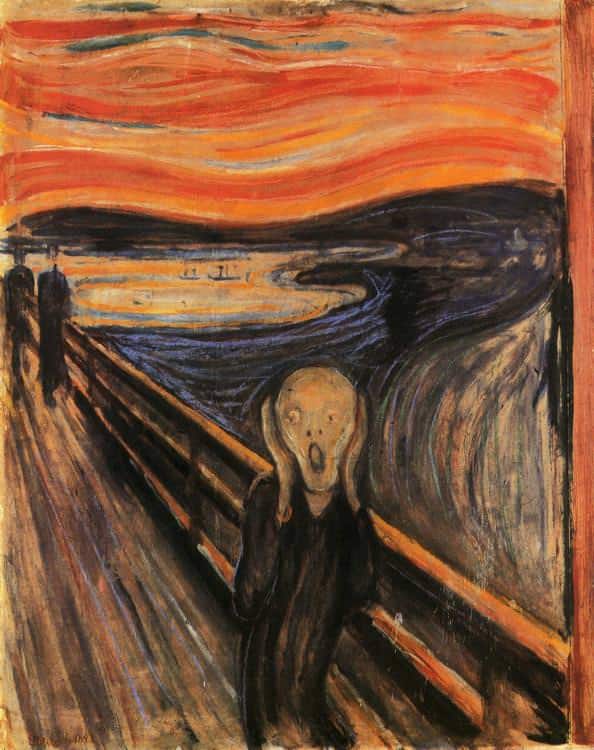

The polar aims of Impressionism and Expressionism sundered the Keatsian yoking of beauty and truth apart; Impressionism sought out visual pleasure while Expressionism explored the concept of truth with all its difficult and perturbing implications. Edvard Munch wrote: “… in my art I attempt to explain life to myself”. Bacon also sought to do this, to elucidate sexuality, what it is to exist and, through an aesthetic sublimation of horror, render the brute empirical into the ‘aesthetico-empirical’ edifice that shares much with the Aristotelian vision of cathartic tragedy – by Bacon we are almost drowned in pain and then released by our own perception of the ingenuity of the edifice.

Munch’s veering on occasion toward the symbolic on his quest, i.e. the depiction of the ideational world of emotion and the psychological is completely subverted by Bacon’s world of fleshly agony. He institutes a ‘state of flesh’, as opposed to the Expressionist ‘state of mind’, in which there is no room even for coherent emotion per se but rather that which inhabits the paroxysmal and isolated interstice between the sensation of pain and its verbalisation. In this way, Bacon adopted the compositional machinery of Expressionism but none of the sanitation of pure emotion or thought – bodily pain contaminates the interior in an anti-Cartesian mutual adulteration of the ‘ghost and the machine’. Bacon often operates at the moment of inhalation before the emission of a scream or the establishment of the sense of sensation.

Compiled by: Shane Lewis

Great write up – I confess I have thought of some new entries for my own blog. Lots of interesting content here. Keep it up.